Dear friends,

I’m excited to share a condensed written version of my January 29, 2025, lecture at Emory Law School, where I examined the historical ties between race, poverty, and inequality in modern America.

First, I want to thank Professor Darren Hutchinson, Professor of Law and the John Lewis Chair for Civil Rights and Social Justice at Emory Law School, for his kind invitation and leadership in advancing the critical work of the Center for Civil Rights and Social Justice. It was an honor to join colleagues at Emory Law at the launch of the center’s spring 2025 lecture series on economic justice.

The Center’s work takes a broad, inclusive view of civil rights and social justice, recognizing the deep connections between race, gender, disability, and other structural inequities that shape the economic landscape. The areas they focus on—democracy, criminal law, health disparities, education access, and environmental justice—are all profoundly tied to the issue of economic justice in America. In this lecture, I delve into what economic justice really means, how it compares to other legal conceptions of justice, and why our current legal frameworks often fail to embrace a more expansive vision of what economic justice could and should be.

I hope these insights spark reflection on how we can push the boundaries of economic justice, both in legal theory and in practice. I am breaking this content into two parts.

Part I below explores how economic justice in America is deeply intertwined with racial and structural inequality, tracing its historical roots from Reconstruction through the Civil Rights Movement and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s critique of capitalism, ultimately calling for a transformative approach to justice beyond mere legal equality.

Part II will discuss a conceptual framework of racial capitalism that I am developing that describes its operation in society as an engine. In this framework, the so-called essential worker, often from marginalized racial and ethnic groups, is treated as expendable fuel, cycling through phases of intake, compression, combustion, and exhaust.

To begin, what do we actually mean when we say “economic justice” in America?

The Promise and Failure of Reconstruction

One might begin a conversation about economic justice in the United States by reflecting on a particularly contentious moment in the nation’s history: the period immediately following the abolition of chattel slavery.

It was during this era, in the wake of America’s bloody Civil War, that the promise of Reconstruction emerged as a profound challenge to the existing legal, political, and economic systems built by slavery. It offered an opportunity to radically reimagine democratic citizenship, building on Enlightenment-era ideals of equality and freedom, while also moving beyond the limited confines of property, contract, and White supremacy.

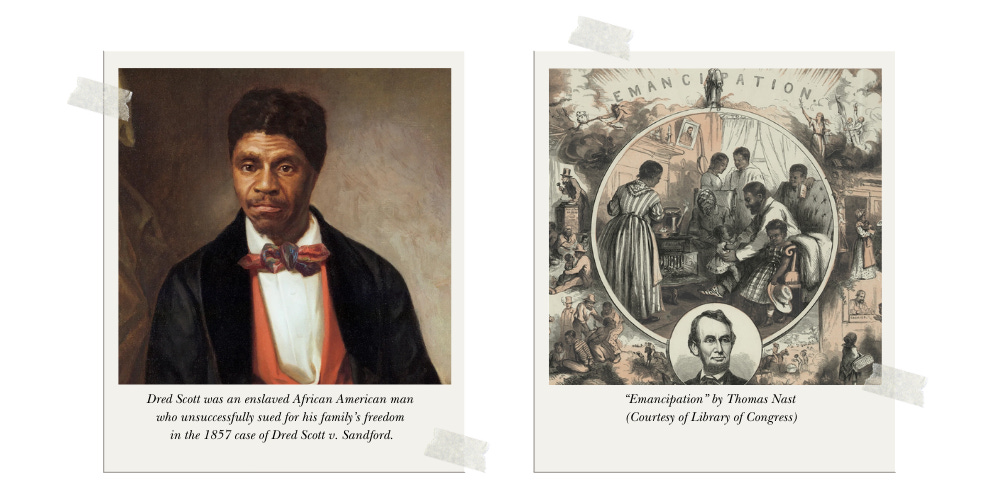

The Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, which abolished slavery and granted equal protection under the law to all citizens, did more than simply overturn Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Recall, in that 1857 Supreme Court ruling, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney had infamously declared that African Americans, whether free or enslaved, could not be citizens, arguing that they had long been regarded as “beings of an inferior order,” unfit to associate with the White race in social or political contexts, and therefore possessed “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” Taney’s opinion in Dred Scott justified the denial of Black Americans’ rights by framing their status as subordinate to the interests of White society.

Beyond acknowledging the inherent dignity of Black Americans, the Reconstruction Amendments revealed the fundamental instability of citizenship as a political and legal concept in a society still structured by racial and economic hierarchies.

Citizenship Before and After Abolition

Before abolition, U.S. citizenship was neither stable nor uniform, existing as a fragmented terrain where rights and privileges varied drastically across both geographic and racial lines.

In Southern states like Virginia and South Carolina, where the plantation economy produced roughly 75% of the world’s cotton, citizenship was explicitly racialized, reserved for White Americans alone. The law and political economy of slavery in the South rendered Black citizenship fundamentally incompatible with the region’s political and economic structure, as the institution of slavery relied on the subjugation of Black people to maintain its power and profitability.

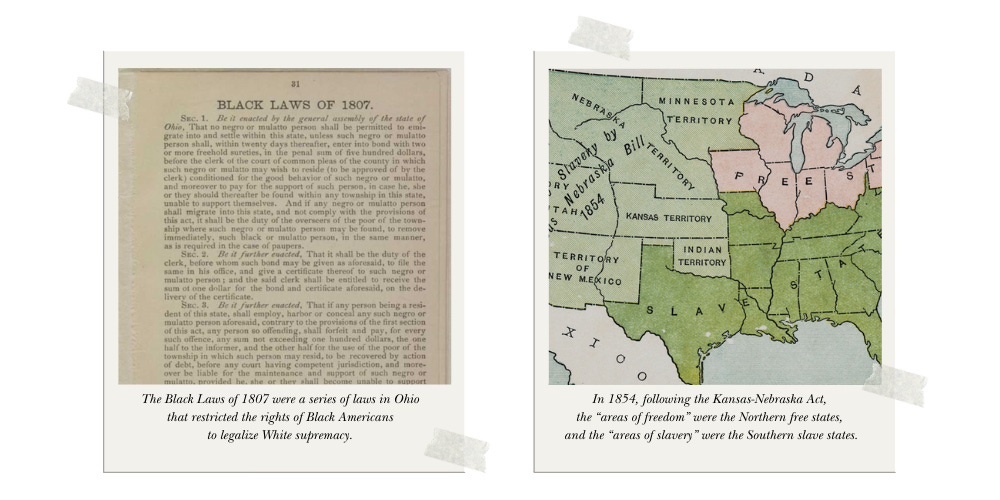

Yet, even in Northern states, where abolitionism was gaining momentum, Black citizenship remained heavily restricted. While states like Massachusetts and Vermont did grant limited voting rights to Black men, discriminatory “Black laws” persisted, further underscoring the racial boundaries of citizenship. These laws imposed restrictions on Black people’s mobility, education, and participation in civic life, creating a patchwork system of civil rights that varied widely across the country.

In Ohio, for example, the state constitution declared that “all men are born equally free and independent,” yet laws that denied Black Ohioans the right to vote or testify in court starkly contradicted this ideal.

As a result, Black citizenship remained precarious even in states that were nominally opposed to slavery. Political compromises such as the Missouri Compromise, the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act attempted to reconcile Southern property interests with Northern ideals of equality.

However, this fragile balance ultimately broke down under the strain of sectional tensions, leading to the outbreak of the deadliest war in American history, the Civil War.

The Freedmen’s Bureau and Reconstruction’s Promise

The establishment of the Freedmen’s Bureau in March 1865 represented a bold and transformative intervention in a fraught social and political landscape. Supported by Radical Republicans, the Bureau sought to empower “all loyal refugees and freedmen” by providing resources for self-sustaining citizenship, including food, healthcare, housing, education, and employment.

This initiative was an ambitious vision of government intervention aimed not only at granting legal freedom but also at providing the tangible material means for Black Americans and poor White Americans in the South—many of whom were war refugees—to experience true liberty.

In this way, the Bureau directly addressed economic injustice, focusing on ensuring that citizens had the necessary support to build stable livelihoods in the war’s aftermath, rather than simply securing their legal status and an abstract promise of equality of opportunity.

However, this promise was rapidly undermined. President Andrew Johnson opposed the Freedmen’s Bureau, and conservative forces swiftly regained economic control. Systems like sharecropping, which bound formerly enslaved people to the land under exploitative conditions, recreated the very dependencies that emancipation had sought to dismantle.

Even more, a violent campaign of Redemption, marked by harassment by local law enforcement, racial terrorism from the Ku Klux Klan, and systemic economic marginalization, aided by the system of convict leasing, effectively nullified the transformative potential of Reconstruction.

Economic Justice and Human Dignity

In this context, economic justice must be understood as something far beyond mere procedural equality or access to opportunity. It requires active political intervention to redistribute economic power, challenge entrenched hierarchies, and create substantive opportunities for individuals to exercise economic agency.

As Reconstruction-era legislators like Senator Charles Sumner and Representative James Ashley argued, citizenship involves more than formal legal recognition of equality under the law. It necessitates the substantive capacity for meaningful participation in political and economic life.

This vision of citizenship demanded that individuals not only be granted civil rights but also be equipped with the social and economic resources and opportunities to fully engage in the myriad systems that shape society.

Economic justice, within this framework, extends beyond individual transactions or legal mechanisms in the private market to critically examine the fundamental structures of public life that perpetuate economic marginalization. It pushes for a deeper understanding of the systems and power dynamics that shape economic inequality.

The question is not simply whether laws and public policies impacting the economy are race or gender neutral, but whether they actively facilitate or obstruct the material conditions necessary for human flourishing.

In other words, economic justice requires a focus on how laws and policies either support or hinder the ability of individuals to lead fulfilling and equitable lives, addressing the root causes of inequality rather than just its symptoms.

Contemporary Economic Injustice: Food Insecurity

When we begin to understand economic justice in this way, contemporary economic injustices, such as food insecurity, cannot be understood simply as the result of marketplace failures. Instead, they are deeply rooted in the legacies of antebellum legal, political, and economic systems.

During slavery, enslavers deliberately restricted the ability of enslaved people to produce their own food, confining them to segregated living conditions on the plantation where food was cheap, unhealthy, and intentionally designed to keep them dependent. Hunger was used as a tool of labor control, keeping the enslaved population in a state of perpetual vulnerability.

It’s not a stretch to argue that this same dynamic persists today in what we refer to as “food deserts” and “food swamps”—areas predominantly inhabited by low-income Black and Brown communities in urban neighborhoods across the United States. These neighborhoods face limited access to fresh, nutritious food while being inundated with cheap, unhealthy options, reinforcing cycles of economic marginalization and poor health outcomes.

The structural patterns that began during slavery continue to impact these communities, perpetuating injustice through food insecurity.

Economic justice requires recognizing that systems of inequality are not only reflected in economic structures but are actively reproduced by them. It envisions a form of citizenship rooted in human dignity—one that goes beyond merely respecting others’ rights to creating economic conditions that allow all people to fully develop and thrive.

This vision of justice is not merely about redistributing resources. It calls for a complete reimagining of economic relationships. It challenges the limiting belief that market mechanisms alone can effectively address inequality. Rather than seeking incremental reforms to existing economic systems, it demands their fundamental transformation.

The economic struggles of Reconstruction were not just historical events. They remained unresolved well into the 20th century and persist today. For example, when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. rose as a leader in the civil rights movement, America was still struggling to answer a critical question:

How can the abstract concept of equal protection under the law, as fortified by the Fourteenth Amendment, be translated into meaningful, real-world economic opportunities for all Americans?

King’s Radical Shift Towards Economic Justice

King inherited America’s legacy of (un)equal protection under law and its harsh reality of economic injustice. By the time he began his activism, systems like sharecropping, discriminatory labor practices, and economic marginalization had solidified into new forms of structural inequality—what we now refer to, often too simplistically, as Jim Crow.

The civil rights movement, King understood, couldn’t be content with legal desegregation alone. It had to confront the deeper economic systems that sustained racial oppression. His brilliance lay in recognizing that constitutional struggles over citizenship weren’t simply abstract debates about colorblindness. They were rooted in the lived realities of economic deprivation and the denial of human dignity.

The struggle for equality, therefore, had to go beyond legal reform and challenge the economic structures that perpetuated racial injustice. This deeper understanding of economic inequality became central to his vision. He saw how the economic system continued to deny Black Americans full citizenship, thereby dishonoring the very promise of equality in the constitution.

King’s evolving understanding of economic justice linked historical analysis directly to the core of his message. His vision was not merely an extension of the civil rights movement but also a sharp critique of the capitalist system that perpetuated both racial and economic inequality.

While King is often remembered for his calls for racial equality, his most radical vision emerged in the final years of his life. Beyond the dismantling of legal segregation, he began to develop a deep critique of American capitalism.

His revolutionary approach to economic justice not only challenged the political systems that supported racial oppression but also took aim at the economic structures that sustained inequality, calling for a fundamental transformation of the nation’s political economy.

King’s Radical Economic Vision

King’s journey from civil rights leader to advocate for economic justice was not a mere accident. It was a deliberate and thoughtful evolution shaped by his growing understanding of the deeper issues at play.

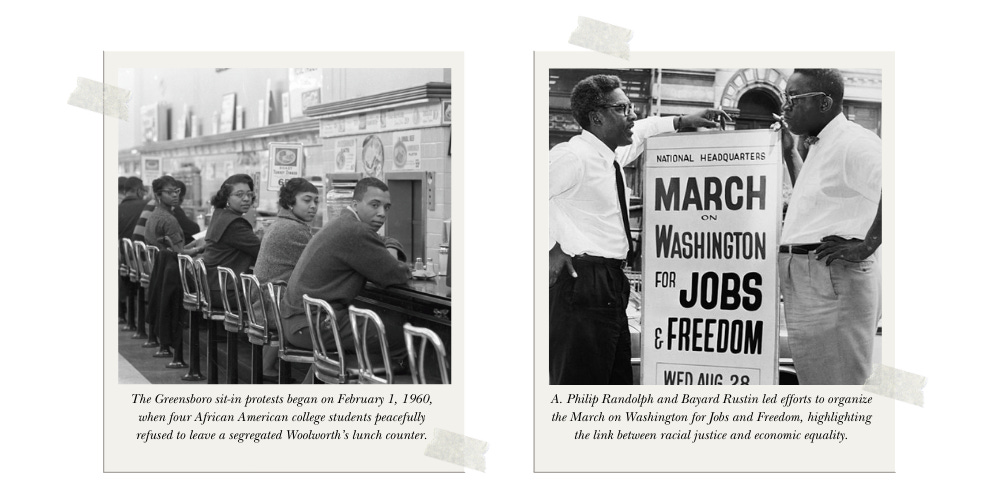

Initially, his focus was on ending legal discrimination in places like restaurants, buses, and schools. However, as his activism progressed, King recognized that formal legal equality alone was insufficient for achieving true economic justice.

By 1963, his “I Have a Dream” speech already began to hint at this broader vision, referencing America’s “bad check” of economic opportunity—a check marked with “insufficient funds,” underscoring how racial equality had been denied in the economic realm.

The turning point in King’s thinking came as he witnessed the persistent inequalities that endured even after the formal end of legal segregation. He realized that true freedom required more than just civil rights. It demanded economic opportunity and financial security.

As he famously asked,

“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?”

This pointed question revealed his growing understanding that legal desegregation alone could not ensure real, lasting freedom. King saw how economic systems were designed to perpetuate both racial and economic inequality, recognizing that human dignity was “corroded by poverty” in a society that valued individuals primarily through their economic worth as laborers.

King came to believe that the existing economic structure was fundamentally incompatible with genuine human dignity and the ideals of democracy. True equality, he argued, could only be achieved by transforming both the political and economic systems that upheld racial oppression.

King’s Economic Justice and the Poor People’s Campaign

In 1968, the Poor People’s Campaign marked King’s boldest effort to reimagine American democracy. It was not merely a push for anti-poverty measures, but a call for the comprehensive reconstruction of social and economic relations in the United States.

The campaign sought to build a multiracial movement that united people in challenging the structural inequalities embedded within the U.S. political and economic system. Its vision was radical, proposing mass demonstrations that would bring together people of all races who shared a common experience of economic oppression in the labor market.

The goal was to expose and dismantle the systemic barriers that prevented full citizenship and human dignity. Economic justice, in this vision, went beyond wealth redistribution. It called for a fundamental shift in how society valued and treated its most vulnerable people—its workers.

The Poor People’s Campaign was about reimagining citizenship itself, emphasizing that true freedom in a liberal democracy required guaranteed access to food, affordable housing, employment with a living wage, and broader economic opportunities for all.

The findings of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Kerner Commission in 1968 echoed King’s vision. The commission attributed the unrest in American cities to racism and highlighted the role of White supremacy in maintaining systems of economic oppression in urban areas nationwide.

Though King was tragically assassinated before the Poor People’s Campaign could fully launch, his vision remains vital today in understanding economic justice. Housing insecurity, food insecurity, unemployment, and over-policing remain pervasive issues that undermine the well-being of communities across America.

King’s legacy calls us to radically reimagine democracy if we want to achieve economic justice. It challenges us to build a society where the economy serves as the foundation for human dignity, and where all people have the opportunity to truly flourish, free from the systemic barriers that hold them back.

Stay Tuned for Part 2

Thank you for engaging in this important dialogue. Stay tuned for part 2, where we will explore a conceptual framework of “racial capitalism” that I am developing.

In this framework, racial capitalism operates as an engine, where so-called essential workers—often from marginalized racial and ethnic groups—are treated as expendable fuel. Labor is funneled into low-wage, high-risk jobs, exploited through systemic inequities, financially extracted through mechanisms like the prison-industrial complex, and ultimately discarded into “sacrifice zones,” reinforcing racialized inequalities and consolidating wealth and power in the hands of a few.

I look forward to sharing more soon.

In solidarity,

P.S. As always, thank you for reading this edition of Freedom Papers. If you found this piece meaningful, share it with a friend. If it moved you, consider supporting with a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. This creative exploration happens because readers like you believe words and stories matter.

Your support gives me the freedom to write from the heart.

thank you so much for this work. Powerful narrative for understanding the importance of where we are and why its important to get involved with William Barber and the Poor Peoples Campaign today.