The Unfinished Struggle

Race, Capitalism, and Economic Justice in America (Part 2 of 2)

Dear friends,

As we continue to explore the intersection of race, poverty, and inequality in America, I’m excited to share Part II of my mini-series on economic justice, where we delve deeper into the concept of racial capitalism—a lens that offers new insights into the functioning of modern economic systems.

To briefly recap, Part I of this two-part series (both parts originally delivered as a public lecture on January 29, 2025, at Emory Law School) examined the historical roots of economic justice, tracing its connection to systemic inequities, beginning with Reconstruction and the failures of the Freedmen’s Bureau. We also explored how historical injustices—like food insecurity—are not merely the result of market failures, but are deeply intertwined with the legacies of chattel slavery and economic marginalization.

Part II builds on that foundation by expanding on the concept of racial capitalism, which I believe is the engine driving modern workplace exploitation. This framework reveals how marginalized communities—especially those from racially and ethnically minoritized backgrounds—are often treated as expendable fuel in an economic system that thrives on cycles of intake, compression, combustion, and exhaust.

What do I mean by this engine metaphor?

The “essential worker” narrative, which gained prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, serves as a powerful example of this cycle. These workers—overworked, underpaid, and often invisible—bear the brunt of an economic model that profits from their labor, only to discard them when no longer needed.

In other words, racial capitalism operates as an engine where labor is funneled into low-wage, high-risk jobs, exploited through systemic inequities, and financially extracted via mechanisms like the prison-industrial complex. Ultimately, these workers are discarded into environmental “sacrifice zones,” reinforcing racialized inequities and consolidating wealth and power in the hands of a few.

Let’s break this down further.

COVID-19 and Expendable Workers

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted a brutal paradox: while workers were labeled “essential,” they were often treated as expendable. Celebrated as heroes during the darkest days of the pandemic, they were simultaneously treated as disposable human beings, some likely buried in mass graves.

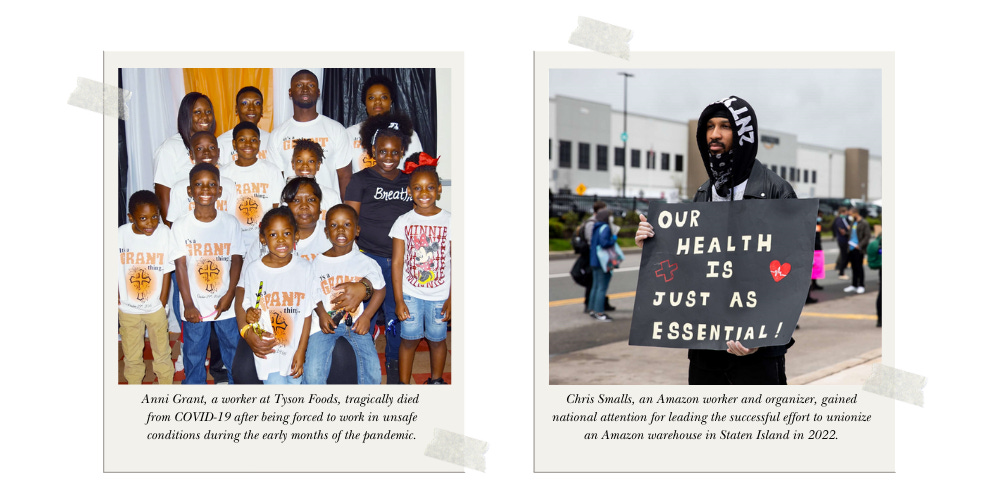

Take Annie Grant, a 55-year-old Black meatpacking worker in Georgia, for instance. Despite showing symptoms of COVID-19, she was pressured to return to work at Tyson Foods, where she eventually died from complications.

Government and corporate rhetoric about “essential workers” rang hollow. Vice President Mike Pence praised their service, while companies like Tyson offered a meager $500 bonus for risking their lives. This exploitation wasn’t limited to the U.S.

In India, thousands of so-called “essential service workers” perished from COVID-19 because they had no choice but to continue working to provide for their families.

This revealed a deeper truth: workers—particularly from minoritized racial and ethnic groups—are too often treated as expendable resources.

At Amazon, workers like Chris Smalls and George Leigh became symbols of a system that prioritizes production over life. Immigrant workers faced even more precarious conditions, like Felix Jiminez, a 56-year-old hog processing worker in Oklahoma who died in a city that didn’t issue stay-at-home orders.

These tragic deaths expose systemic failure. Recognizing workers’ rights to safety isn’t optional—it’s a moral imperative that defines our collective humanity. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the fault lines in our system. We now have a choice.

We can either return to business as usual or build a more just world.

The Engine of Racial Capitalism

What we witnessed with essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic can be understood through the lens of racial capitalism—the systematic extraction of surplus value from racially marginalized bodies, their labor exploited for profit while their lives are devalued and rendered expendable.

To fully grasp this concept, we must place it in historical context. The term “racial capitalism” first emerged in 1970s Apartheid South Africa, where anti-apartheid activists questioned how capitalism would fit into a post-apartheid society.

The term gained prominence in Cedric Robinson’s 1983 work, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, where he used it to challenge traditional Marxist views that treated racism and capitalism as separate but connected systems.

What did Cedric Robinson mean by “racial capitalism”?

While Marxists often frame capitalism as exploiting racial divisions created by colonialism and slavery, Robinson traced racial capitalism’s roots back to European feudalism. There, the racialization of groups like Slavs, Jews, Roma, and the Irish was central to wealth accumulation. Robinson argued that capitalism and racialization were not separate—they were fundamentally linked. White supremacy wasn’t just a byproduct of capitalism; it was essential to it.

To truly understand economic justice today, I argue that we must view racial capitalism not as an abstract theory but as an actively engineered system—an engine of corporate governance machines designed to convert human labor into shareholder wealth, operating through ongoing, insidious phases that continue to perpetuate exploitation.

In a forthcoming article, I describe four phases of the engine.

Phase 1: Intake

The first phase of the engine is the intake phase.

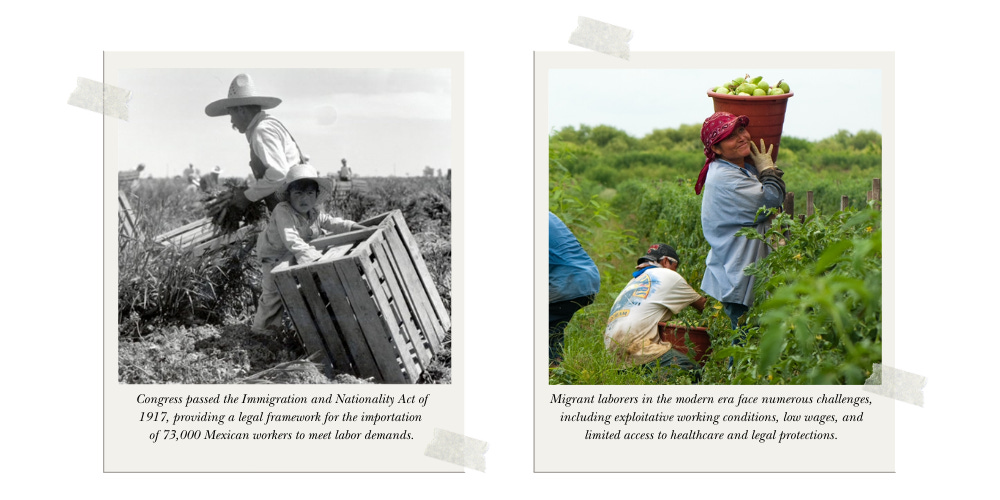

This is where racial capitalism draws in labor through calculated mechanisms of historical and contemporary exclusion. Since the very founding of the United States, the labor market has been deliberately designed to marginalize specific populations, creating a funnel that channels marginalized groups into exploitative labor conditions.

From the onset of European colonization, the justification for land expropriation rested on dehumanizing doctrines like terra nullius and the “doctrine of discovery,” which framed Native lands as unclaimed and indigenous people as disposable.

This logic was mirrored in the enslavement of Africans, who were not simply categorized as inferior but legally reduced to property—commodities that could be bought, sold, and forced into labor. The economic structures established during this period were foundational in setting the stage for continued exploitation, embedding a racialized economic order that still dictates labor relations today.

The intake stroke of racial capitalism isn’t only about overt violence. Today, it operates through more subtle, yet equally devastating, processes.

Residential segregation, underfunded schools, limited access to skills training, and systemic hiring discrimination all funnel marginalized communities into what we might call the true “Essential Work” of capitalism. These jobs are typically low-wage, high-risk, and offer little autonomy—designed to maximize corporate profit while stripping away basic human dignity.

What’s critical to understand is that this isn’t some unintended consequence. It’s a deliberate, calculated system that channels labor into specific pathways—pathways that exclude rather than include, leaving many trapped in cycles of exploitation and economic marginalization.

Phase 2: Compression

The second phase of racial capitalism is compression.

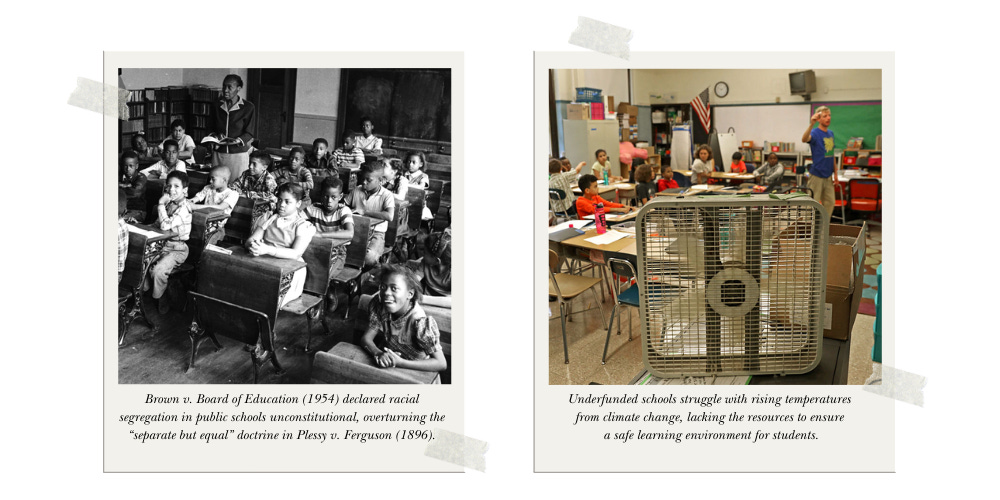

In this phase, the engine’s piston rises, forcing the labor mixture through a process of exploitation and expropriation. One of the most insidious mechanisms in this phase is educational inequity. Schools in predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods receive far less funding than those in wealthier, predominantly White areas.

On average, school districts in these marginalized neighborhoods receive $23 billion less in funding than those in more affluent districts. This funding gap is not an accident. It is the result of policies that purposefully funnel resources away from these communities, leaving them with inadequate facilities, overcrowded classrooms, and fewer educational opportunities.

The consequences of this educational disparity are profound and long-lasting. By denying children in these communities the resources they need to succeed, society creates a workforce that remains economically vulnerable. With limited access to quality education, young people in these communities are often pushed into low-wage, high-risk jobs, continuing the cycle of exploitation and entrenching racial and economic inequalities for generations.

This compression is not just an economic issue—it is racialized. The myth of meritocracy serves as a powerful tool in perpetuating the idea that persistent marginalization is a result of individual failures rather than systemic oppression. This narrative frames the continued concentration of Black Americans in low-wage, high-risk employment as a consequence of personal choices, rather than the product of centuries of deliberate exclusion.

By focusing on individual shortcomings, society ignores the broader structural forces at play—forces that systematically deny marginalized communities access to wealth-building opportunities, quality education, and upward mobility.

The neoliberal revolution of the late 20th century further exacerbated this compression. As labor protections were dismantled and industries were deregulated, the foundation for fair wages and job security was eroded. In its wake, entire communities were left fighting to survive in an increasingly precarious labor market.

Rather than being empowered to challenge the system that kept them trapped, these communities were forced into survival mode, where meeting basic needs took precedence over questioning the inequalities that underpinned their struggles. This shifting of focus from resistance to survival has perpetuated a cycle that reinforces racial and economic inequities for generations.

Phase 3: Combustion

The third phase is combustion—the stage in which the accumulated potential energy of compressed labor is violently released.

In this phase, the extraction of value intensifies, particularly through financialization, a central mechanism of racial capitalism. As corporate power consolidates, workers—the very fuel that powers the engine—are systematically excluded from the wealth they help generate. Instead, their labor is commodified and exploited to maximize profits for those at the top.

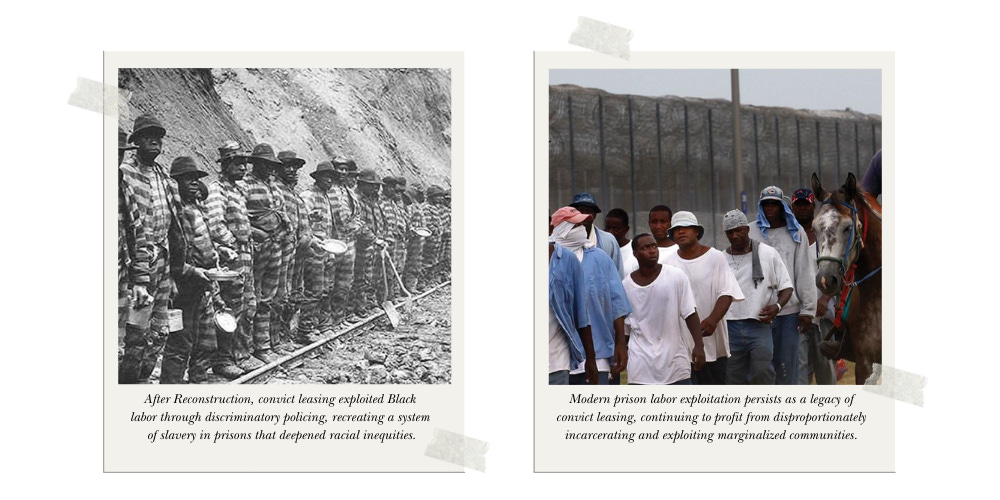

A stark example of this exploitation is the prison-industrial complex. Approximately 800,000 incarcerated individuals are forced to work, generating around $11 billion annually. Yet, they earn a mere 13 to 52 cents per hour, with some working for no compensation at all. This system of unpaid or underpaid labor—modern day slavery in many cases—highlights how racial capitalism not only extracts value from labor but also traps people in cycles of disenfranchisement and poverty.

This modern system of labor extraction mirrors the convict leasing system after the Civil War, which re-enslaved emancipated Black Americans for profit. The Thirteenth Amendment’s exception clause, which allows slavery and involuntary servitude as punishment for crime, legitimizes this exploitation.

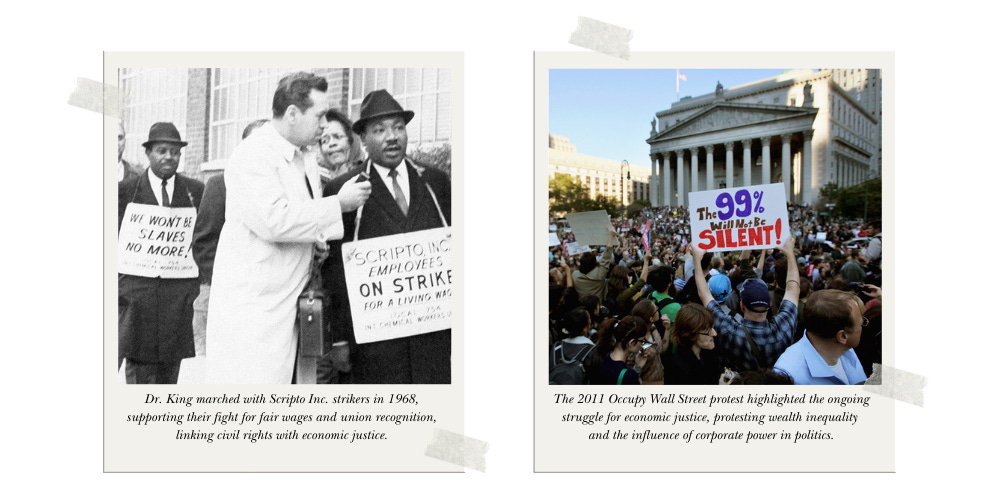

Combustion is not just about extracting labor. It’s about consolidating wealth and political power in the hands of a few. Through mechanisms like voter suppression, felony disenfranchisement, and corporate money in politics, democratic participation is systematically eroded.

Decisions about wealth distribution and political power are made by corporate executives and shareholders, not by the workers whose labor fuels the system. This phase demonstrates how racial capitalism actively reinforces inequality and undermines efforts for broader political and economic justice.

Phase 4: Exhaust

The fourth and final phase is exhaustion—the stage where exploited labor is discarded once it is no longer deemed useful.

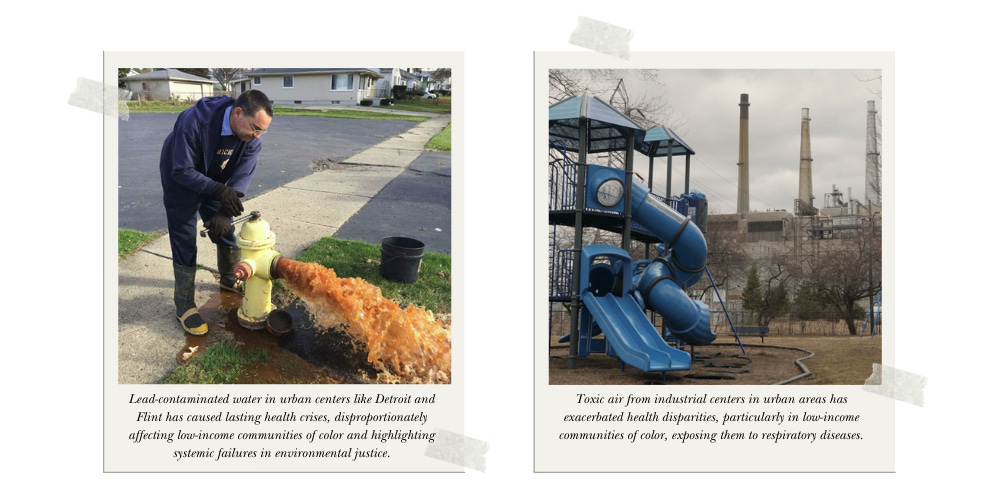

At this point, marginalized workers are pushed into what scholars call “sacrifice zones”—communities that absorb the worst consequences of environmental and economic devastation. These are the neighborhoods with toxic waste sites, polluted air, and crumbling infrastructure, where disinvestment and environmental harm go hand in hand.

Whether through mass layoffs, lack of healthcare, or exposure to hazardous conditions, workers who once powered the economic engine are cast aside, left to navigate the wreckage of an unjust system.

Once industrial hubs, cities like Detroit now represent the consequences of capital abandonment. Once thriving, they are now plagued with lead-contaminated water, toxic air, and perpetual economic and environmental peril.

The environmental justice movement has long highlighted these inequities, from the devastation of indigenous lands in the Amazon rainforest to the pollution in Flint, Michigan. In these spaces, the damage is not just environmental but existential—communities are abandoned, left to suffer the consequences of corporate greed and indifference.

Reimagining Economic Life

The engine of racial capitalism is not a malfunction.

It is working exactly as it was designed to work. Its genius lies in its ability to perpetuate inequality, converting human potential into corporate profit while maintaining the illusion of neutrality, fairness, and meritocracy. The system thrives because it allows those in power to hide behind these illusions, perpetuating racialized labor exploitation while avoiding accountability.

However, our task is not to repair this machine. Our task is to fundamentally reimagine how we organize economic life. We must center human dignity over shareholder wealth, solidarity over competition, and collective well-being over individual extraction.

We must resist the systems of power that perpetuate this racialized exploitation, and instead, build a world where justice, equity, and solidarity reign.

This is not merely an economic challenge.

It is a moral challenge that demands our collective imagination, resistance, and transformative action. It is time for us to reimagine a world beyond the engine of racial capitalism, a world that recognizes the inherent worth and dignity of every individual, regardless of race or background.

Let us stand together, not just in opposition to this system, but in the pursuit of something far greater—a more just, equitable, and sustainable future for all.

In solidarity,

P.S. As always, thank you for reading this edition of Freedom Papers. If you found this piece meaningful, share it with a friend. If it moved you, consider supporting with a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. This creative exploration happens because readers like you believe words and stories matter.

Your support gives me the freedom to write from the heart.